About the Author

Daniel Lee

Senior Economist, CBI

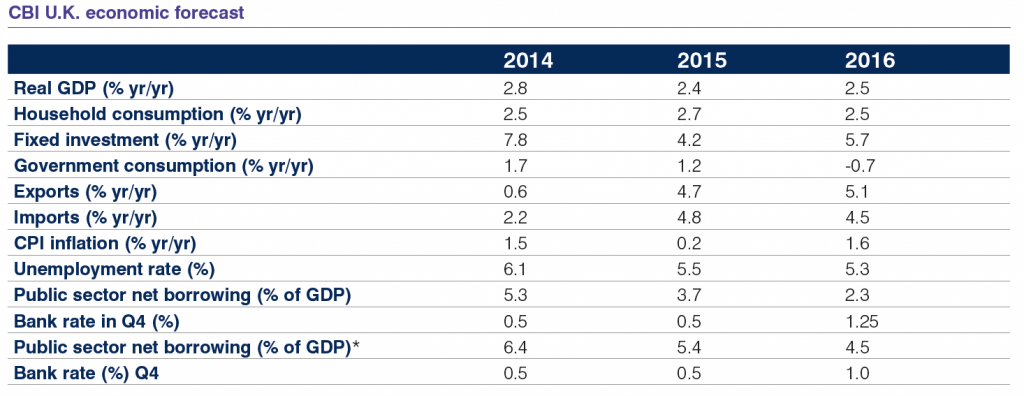

The U.K. economy put in a robust performance in 2014, with a healthy growth rate of 2.8% making it the fastest growing economy in the G7. Sustained quarterly growth over 2013 and 2014 has helped to embed the recovery and put the lingering legacy of the financial crisis further in the past, with GDP in Q1 2015, 4% above its pre-crisis peak.

Nonetheless, the road from recession to recovery since 2008 has been protracted and has left deep scars, with the economy operating over 15% below the pre-crisis trend. Although recovery now seems firmly established – barring any major shocks – the pace steadied over 2014, from 3.6% (annualized) in Q1 to 2.5% in Q4, a rate close to the pre-crisis trend, so that gap may not close much further.

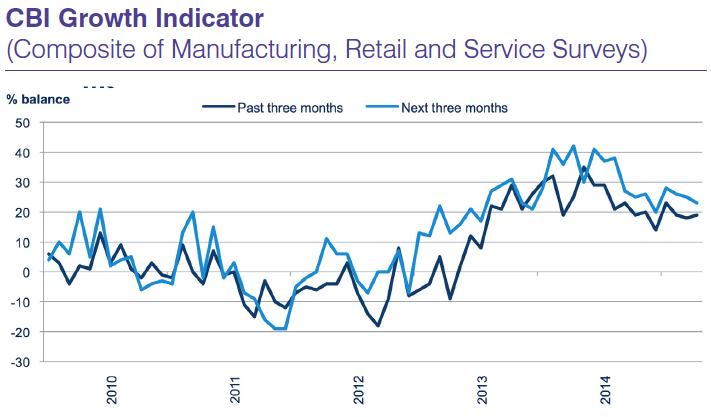

In the main, the easing of momentum refl ects a weaker contribution from investment and a sharp pick-up in imports of both goods and services, consistent with a return to more sustainable, trend growth rates. We see a further dip in growth to 1.2% in Q1 2015 as a temporary blip, given that our business surveys report that firms are experiencing slower but solid growth and, in the large services sector, improved prospects for the spring. We expect U.K. GDP growth to rebound in the second quarter and return to around 2.5% per quarter thereafter, helped by a boost from lower energy prices (see box) – but there are plenty of domestic and external factors to keep an eye on.

INVESTMENT HAS PLAYED ITS ROLE…

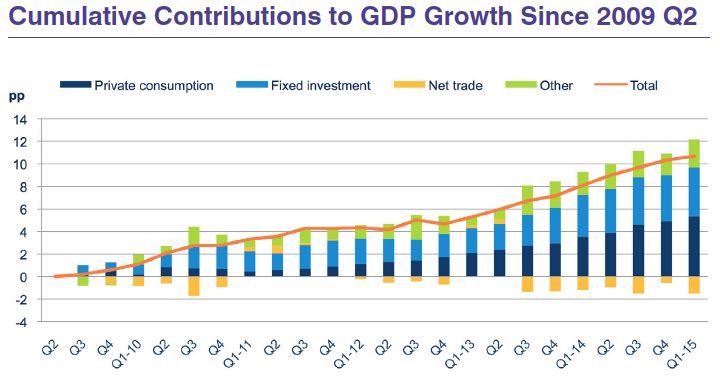

One of the key concerns during the recovery has been the composition of growth. In the early stages of the recovery, it appeared that the already indebted consumer was doing all the heavy lifting in terms of domestic demand. A year ago, the then data vintage showed the consumer accounting for almost 90% of overall economic growth in 2013. With negligible wage growth, and little sign of a material improvement in investment and trade performance, the sustainability of the recovery appeared at risk.

Fast forward to today, and the picture has been changed by improvements in credit availability, rising corporate and consumer confidence, and a number of data revisions. Consumer spending is now recorded as having accounted for only around 65% of growth in 2013, similar to its share in GDP, and for a little over half in 2014. Meanwhile, fixed investment began to pick up in 2013 (growing 3.4%) and surged 7.8%, accounting for around half of overall growth in 2014, the strongest in over twenty-five years. The more balanced picture bodes better for the durability of the U.K.’s recovery.

Notably, private business investment has picked up the slack from investment in homes, still yet to fully recover after collapsing over 2008-9; and in government investment, which was cut back in the early years of the outgoing coalition government. In fact, business investment has looked more robust in the recovery than it did in the run-up to the financial crisis. Having fl at-lined for much of the decade after 1997, it has grown every year since 2010 by an annual average of 5.8%, taking it almost 9% above the pre-recession peak in Q1 2015. Business investment now accounts for some 10.5% of U.K. GDP, more than it did at the eve of the financial crisis.

…BUT TRADE HAS FAILED TO CONTRIBUTE…

However, there remain some crucial elements missing from the U.K. recovery to date. Trade is one, having failed to make a material positive contribution to growth in either 2013 or 2014. Indeed, Britain’s trade deficit widened in 2014, thanks to a combination of sluggish exports growth (0.6%) and more vigorous imports growth (2.2%), as domestic demand recovered. Going forward, net trade performance is unlikely to do much better, even with a modest recovery in export growth, since if the U.K. continues to out-perform its neighbors, its imports will continue to rise firmly.

Undoubtedly, a large part of the underperformance of British exports in recent years has been due to the fact that the bulk of its exports go to the crisis-ridden Eurozone (38% of the total in 2013, from 45% in 2007), while re-balancing toward faster-growing markets has proceeded only slowly (the share going to China rose from 1.5% to 3.2% over the same period). Geographic proximity, and the fact that Britain’s comparative advantage lies particularly in services exports more suited to the demands of high-income countries, have proved powerful forces – for example, the U.K. still exports half as much again to the Republic of Ireland as it does to China. Even a drop in the trade-weighted value of Sterling by nearly a quarter over 2007-9 has provided little obvious fillip to export growth, perhaps in part because of stiff competition from the neardeflationary Eurozone.

The trade performance has had consequences for the sectoral balance of growth, since exports matter far more to manufacturing than they do to services. Notwithstanding a few success stories, notably in motor vehicles, British manufacturing overall remains almost 5% smaller than it was before the recession and its growth pretty much stalled in late 2014. The CBI’s Industrial Trends Survey makes it clear that weak demand from abroad is mostly to blame – domestic new orders have been expanding robustly in 2014 and so far in 2015, while export new orders have generally been flat or falling. Manufacturers’ concerns about “political/economic conditions abroad” have eased of late, but are being replaced by worries about a pound that is once again on the rise – our survey reported that competitiveness in the E.U. fell at the second-steepest rate on record in the three months to April.

Ultimately, net trade has a limited impact on overall growth, being a much smaller component of GDP than consumption or investment (the U.K.’s exposure to international trade is about normal for an economy of its size, but much less than that of most smaller countries in Europe). However, sluggish exports have left the U.K. economic mix more tilted towards domestically-focused services than ever, and contributed to a record current account deficit (though sluggish overseas investment performance is a bigger factor here). Both factors could leave the country more vulnerable to shocks than it would have been otherwise.

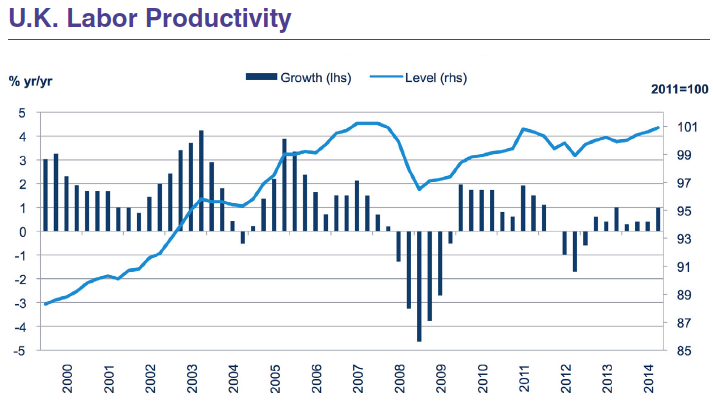

…AND PRODUCTIVITY NEEDS TO START RECOVERING

The need to shake off the protracted slump in productivity growth that has plagued the U.K economy since the recession will be even more fundamental to its growth prospects in the coming years. The U.K. has enjoyed a remarkable employment performance in recent years, considering the depth of the recession and slow pace of recovery, with the total number employed now 4.6% higher than it was before the recession. However, the flip-side of resilient employment through a record post-war slump is weakened labor productivity. Even after over two years of recovery, in Q1 2015 British workers still produced 1.5% less per hour than they did before the recession, and fully 13% less than they would have if the economy had continued on the pre-recession trajectory. And this measure of productivity has not improved since 2013 along with the overall economy – in fact, hours-based productivity edged down 0.2% between 2012 and 2014.

The persistence of the slump has prompted much headscratching among analysts about a so-called “productivity puzzle” and little consensus about its cause. A variety of factors seem to be at play. Some are of a structural nature: notably the long-term decline of the offshore oil & gas industry and the retrenchment in the U.K.’s large financial services sector following the crisis, with other industries not yet able to take up the slack. But other factors seem related to the economic cycle: weak wage growth may have prompted a shift away from investment in capital stock towards laborintensive business strategies; firms may have been putting effort into maintaining their relative competitive position, even though overall demand and output has been weak; and headline strong employment growth hides some remaining under-employment and worker misallocation, with many stuck in part-time roles or turning to self-employment.

Whatever the causes of the slump, productivity now matters more than ever in this recovery, since with unemployment now below 5.5% it cannot be driven much further by increases in the number of people in work – the Bank of England estimate the U.K.’s equilibrium unemployment rate to be 5.1%. Any assessment of the outlook for the U.K. depends crucially on how productivity is expected to perform over the next few years. Some of the cyclical factors holding back productivity should ease as the economy exhausts its remaining spare capacity, but it is likely that they have done significant persistent damage. Structural factors will prove longer-lasting and tougher to crack, but there are at least signs that they will increasingly come to be seen as a key priority for the new government alongside deficit reduction, with a “productivity plan” promise for its first budget. We think that productivity will start to revive over the next couple of years, but that growth is still likely to fall well short of its pre-crisis rates (at 1.2% and 1.6% in 2015 and 2016, compared with 2% per annum over the decade to 2007).

The possibility that even this apparently modest forecast is not realized is one of the key downside risks to the U.K. outlook in the next few years. But with our understanding of the U.K.’s productivity performance so incomplete, the risk actually runs both ways – a firmer-than-anticipated recovery in productivity is possible and would further support income and output growth.

RISKS TILTED TO DOWNSIDE BUT RECOVERY LOOKS ESTABLISHED

Overall, however, the risks to the U.K. remain tilted to the downside. Many of these are international: the oil price could rebound faster than expected; Greek exit from the Eurozone could destabilize the currency union once again; and the normalization of interest rates in the U.S. could lead to volatility in financial markets. On the domestic front, the new government has promised a referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union by the end of 2017 (though it could take place as early as 2016), which could lead to greater business uncertainty and the postponement of investment plans, even if the status quo is ultimately endorsed by voters.

Nonetheless, our view remains that the near-term outlook remains broadly favorable, and that the U.K.’s recovery is well established. We forecast growth of 2.4% and 2.5% in 2015 and 2016, driven by continued investment and a modest recovery in productivity and wages (see table).

Further Information

For further information visit www.cbi.org.uk or contact Daniel Lee, Senior Economist, CBI at daniel.lee@cbi.org.uk

The CBI (The Confederation of British Industry)

The CBI provides a voice for business people and their businesses on a national and international level. We speak for more than 240,000 companies of every size, including many in the FTSE 100 and FTSE 350, midcaps, SMEs, micro businesses, private and family owned businesses, start ups, and trade associations in every sector. Our mission is to promote the conditions in which businesses of all sizes and sectors in the U.K. can compete and prosper for the benefit of all. To achieve this, we campaign in the U.K., the EU and internationally for a competitive policy landscape.